Expanded Jewish museum documents bittersweet refugee era in city

Time£º2020/12/14 10:35:59¡¡¡¡From£ºshdaily

Visitors watch the new exhibitions at Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum after its reopening on Tuesday.

It all started with a refugee child’s bamboo toy rickshaw 10 years ago.

As the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum added exhibits to the rickshaw over the years, it attracted so many visitors that it was forced to undertake an expansion project last year. The renovated museum reopened on Tuesday.

The iconic museum has dedicated itself to telling the stories — both joyous and sorrowful — of the more than 20,000 Jews who took refuge in Shanghai to escape Nazi persecution during World War II.

Located in the Tilanqiao area of Hongkou District, the renovated museum has more than quadrupled its size to 4,000 square meters, creating space for exhibits whose numbers have surged 10-fold to 1,000. Its collection comes mainly from donations by former Jewish residents.

The museum was actually begun in 2007 on the site of the historical Ohel Moshe Synagogue, but it didn’t get its first exhibit until a former Jewish resident donated the toy rickshaw three years later.

Since then, the museum has attracted up to an average 100,000 visitors a year, 10 times more than its earlier days. Visitors are mainly overseas tourists and people seeking their ethnic roots.

New exhibits include personal narratives and paperwork and memorabilia from refugees who cameand lived in Shanghai. New technologies such as multimedia film and transparent screens have been installed to improve the visitor experience.

“The main theme of the expanded exhibitions is to establish a community of a shared future for mankind,” said Chen Jian, curator of the museum.

The Shanghai museum focuses on a “warm-hearted” theme of human compassion and salvation rather than on the horror stories of Nazi persecution that dominate many Jewish-related museum, he said.

Six sections of the renovated museum trace the history of the Jewish diaspora during the war, how refugees came to Shanghai and carved out daily lives, and the contributions they made to the city’s culture in music, painting and photography.

Famed Jewish violinist Alfred Wittenberg, for instance, taught many local young Shanghai musicians who later became virtuosos, like pianist Fu Cong and educator Tan Shuzhen.

“That period of history should inspire the young people of today and contribute to the development of human civilization,” Chen said.

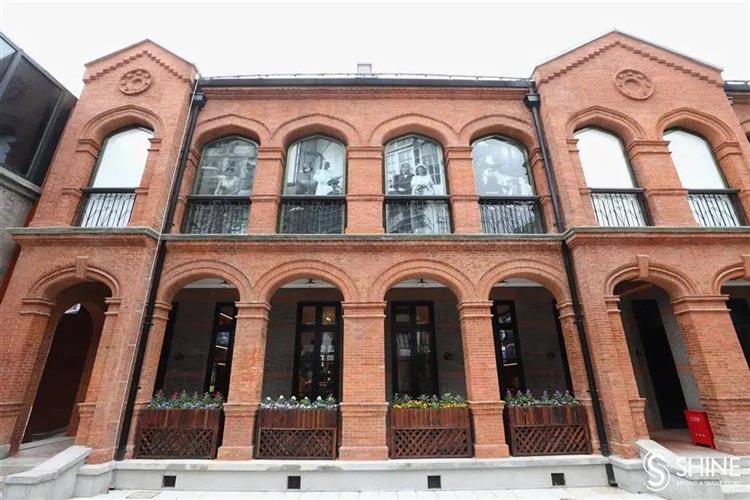

Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum reopens on Tuesday after a major renovation.

During WWII, Shanghai was one of the few cities in the world to receive large numbers of Jewish refugees. Most of them lived in Hongkou after the Japanese occupiers set up a ghetto there in 1943.

After the war, some of the refugees returned to Europe, while others dispersed to the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand or South Africa.

In the beginning, only a memorial hall was planned on the historical site, Chen said. Then an early Jewish visitor told Chen that a memorial hall is for commemorating the dead or for remembering tragedy, and that wasn’t the atmosphere she sensed in Shanghai.

Chen and a team of organizers then turned their idea into a museum and began collecting exhibits from refugees across the world.

“A museum can never tell a story without sufficient exhibits,” Chen said, noting that there were none when the museum first opened.

“It was a challenge for us because most of the valuable memorabilia had already been donated to other Jewish museums around the world or retained as family keepsakes by refugee families,” Chen said.

That changed when Josef Rossbach, a retired doctor who now lives in Hamburg, donated the toy rickshaw to the museum on a visit there in 2010. Now 76, he was born in Hongkou to Jewish parents who fled Nazi Germany in 1939.

“Whenever I held the toy in my hand, my heart beat faster,” he said.

The toy forms part of the new exhibitions, along with Rossbach’s photos and narrative.

Another exhibit displays the five passports that belonged to Ruth Callmann, who fled to China in 1939 with her family. The passports record how she arrived in China from Germany, and then migrated to the United States after the war.

She first showed the passports to Chen in 2009, but declined his request that they be donated to the museum because they were “part of her life,” Chen said.

However, before Callmann died in 2014 in the US at age 96, she asked the trustee of her legacy to donate the one German passport and the four US passports to the Shanghai museum.

“Since then, I have told volunteers working at the museum to listen to Jewish visitors, not just to explain exhibits to them,” Chen said.

The over 1,000 exhibits collected by the museum now span the whole spectrum of refugee life in Shanghai.

They include passports, visas provided by Ho Feng-shan, then Republic of China consul general in Vienna, ship tickets from Europe to Shanghai, and residence and marriage certificates issued by local authorities.

A wedding gown worn by Betty Grebenschikoff, a Jewish refugee who spent 11 years in Shanghai.

A wedding gown worn by Betty Grebenschikoff, a Jewish refugee who spent 11 years in Shanghai and now lives in the US, is one of the new exhibits.

The white classic dress, made from French fabric in a local style, was hand-sewn by her mother-in-law, who worked in a wedding dress store on Nanjing Road. Her third and fourth daughters also wore the dress when they married.

Grebenschikoff initially declined to donate the gown to the museum but changed her mind on her fifth trip to her former residence on Zhoushan Road, near the museum, in 2013.

“I’ve come home again,” said Grebenschikoff of the residence where she lived some 70 years ago. “I have four daughters, a son, grandchildren and great grandchildren, but without Shanghai, I would have nothing.”

The museum renovation also features a new library, with more than 8,000 books donated by Kurt Wick, 82, who fled to Shanghai from Vienna in 1939 with his family when he was just a year old.

The books are mainly about the history, culture and politics of the Jews. Some cover the period when Jews fled Nazi-occupied Europe and found shelter in Shanghai. After being diagnosed with lung cancer, Wick decided he needed a suitable place for his collection for posterity.

“I want to say thank-you to Shanghai for saving me and my family,” Wick said. “I think the books will be useful in Shanghai because you have a lot of students and Jewish visitors.”

The books are in English, Hebrew, German and other languages.

“The museum aims to play a bigger role in academic research and cultural exchanges, so the books are valuable to us,” Chen said.

He added that it would have been impossible for the museum to track down and purchase the books that Wick had spent his life collecting.

An International Advisory Board for the museum has also been established. Twenty-seven members, including historians and descendants of refugees, sit on the board to facilitate academic research, museum operations and international communications.

The members come from China, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Poland and Japan. During the coronavirus pandemic, overseas members and other experts have been using video links to offer suggestion for new exhibits.

A visitor takes photo of the map of the designated areas set up by Japanese intruders for Jewish refugees in Hongkou District.

A visitor browses the new exhibitions at Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum after its reopening on Tuesday.

A new exhibition area at the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum.